In his classes on Indigenous and colonial American history, Professor Nathan Braccio assigns students a research paper that explores the past of a place they know well — or, at least, thought they did.

Through a “history of place” assignment, Braccio asks students to “think about a place in the colonial or post-Columbus period — anywhere in the U.S. that’s significant to them — so they can begin to understand that their place has an Indigenous history, and a history of colonial invasion,” he says, “but also was a place of Indigenous power and, sometimes, Indigenous resistance and persistence.”

“As you look out your window or walk around campus,” for instance, “you’re not just in Worcester, you’re in the Nipmuc homelands. This is a place that became Worcester, and in the process of becoming Worcester, that involved a major set of transformations.”

Knowing the history of a place results in a deeper understanding and connection with it, says Braccio, who joined Clark in fall 2024 as assistant professor of history. “As you look out your window or walk around campus,” for instance, “you’re not just in Worcester, you’re in the Nipmuc homelands. This is a place that became Worcester, and in the process of becoming Worcester, that involved a major set of transformations.”

Braccio developed his own sense of place while growing up in Connecticut and Maine. It informs his scholarship: investigating “the cultural negotiations among Northeastern Indigenous peoples and the New England colonists in the 1600s and early 1700s.”

Integrating his lifelong love of maps

When he entered a Ph.D. program at the University of Connecticut, Braccio hoped to integrate his lifelong love of maps and cartography with a study of escaped, enslaved people in Florida and South Carolina.

“That is where I first began to think about maps in terms of my research and in terms of an alternate geography, the kind of different landscapes that these escaped enslaved people lived in,” he recalls. “To them, a swamp was not a dangerous place but a haven and a refuge, and that set them apart from colonists. That is when I began to think about the existence of an alternative map versus the established English map.”

As he examined historical records, Braccio refocused his efforts on New England, discovering that it harbored a long-hidden, but fascinating, Indigenous history of map-making. “Looking at the place I thought I knew, but in a different way, added resonance and drew me in further,” he says.

Maps play a central role in the colonization and settlement of the Northeast, and in his dissertation research, Braccio first sought to “identify all the ways in which Europeans had erased or ignored Indigenous presence and think of the maps as these tools of erasure.”

But in his study of the maps from the 1600s — many of which are housed in the Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island state archives and identify boundary lines that are still used for towns today — he discovered a different story.

“I quickly found that Indigenous people were present on English maps and land records as sources of authority,” Braccio says. “I wondered why, and that sent me further into studying these broader ideas of spatial culture to try to understand what was going on.”

‘Creating New England, Defending the Northeast’

Braccio’s investigation led to his first book, “Creating New England, Defending the Northeast: Algonquian and English Contested Spatial Worlds, 1500-1700,” soon to be published by the University of Massachusetts Press.

“The common English weren’t map-making people, and they brought that lack of interest with them to the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies,” according to Braccio. Because the early Puritan settlers emphasized community and cooperation, just as they had in England, they had no need for maps when they first settled here in the 1630s.

The Algonquin people, on the other hand, “had a pre-existing mapmaking tradition in the Northeast,” he says. “In fact, they were making maps before colonists made maps, and their mapmaking tradition likely extended long before encountering the English.”

“When an English person held an Algonquin map, writing their own words on it, they transformed the map about sovereignty and Indigenous authority into a record of private English private property and ownership.”

— nathan braccio

In his book, Braccio says, he seeks to describe how “Algonquin expertise about the land and about space gave them influence and power in their dealings with English colonists, who came to the Northeast without an epistemology suited to the new landscape — a system of knowledge that allowed them to understand, to measure, and even navigate the Northeastern landscape. They became reliant on Indigenous people, who were able to use that reliance in various ways.”

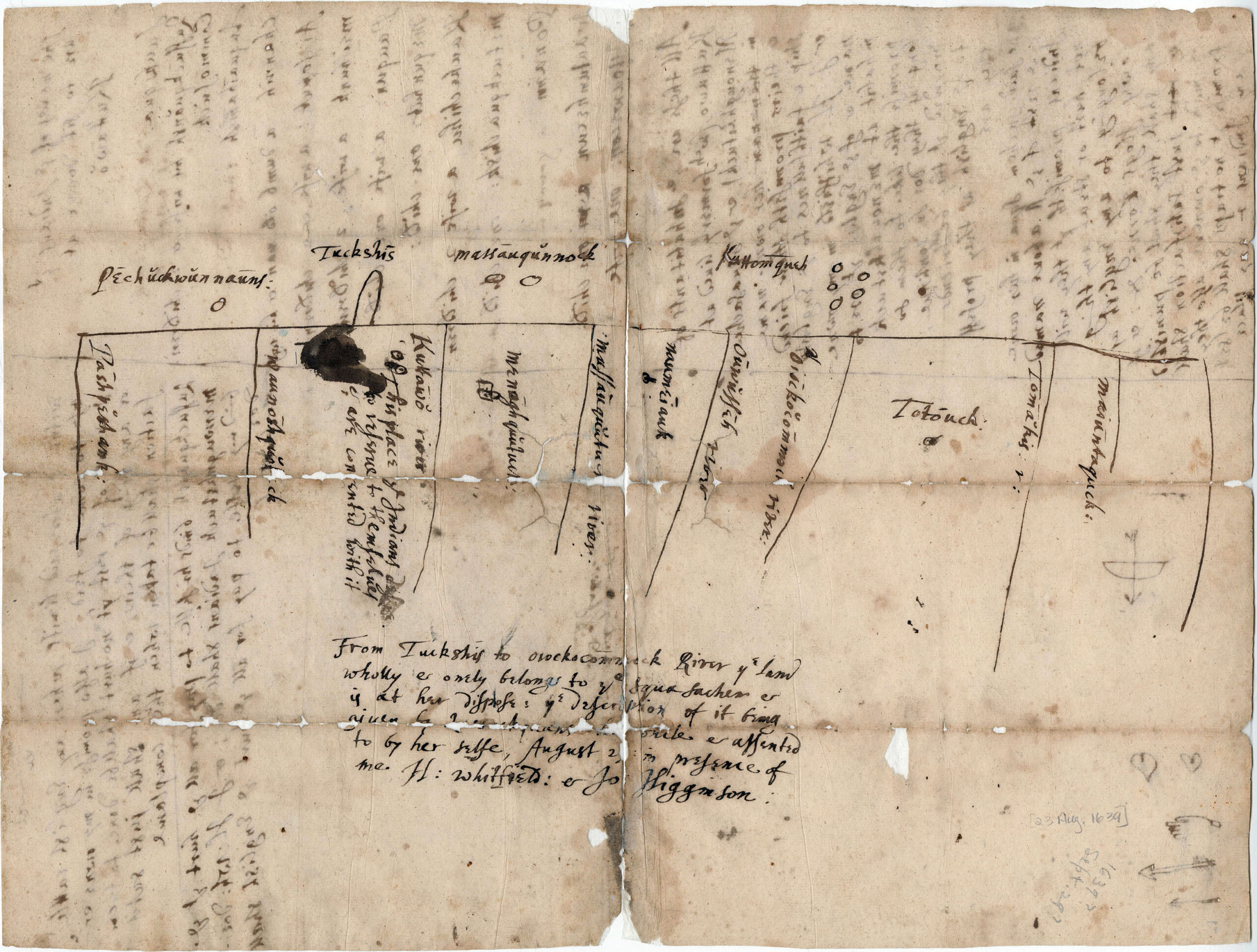

Historical records indicate that the Algonquin first drew maps with charcoal on bark or with rocks in the sand. The earliest, still-existing Algonquin map on paper dates to 1638, according to Braccio.

Sachems — the leaders of Indigenous “polities” — used the maps as diplomatic tools when meeting English settlers and also as a way to declare sovereignty over lands, separate from other Algonquin villages, he says.

“When they encountered English people who didn’t speak northeastern Algonquin languages, they used maps to facilitate cross-cultural communication,” Braccio says. “Maps and this top-down view are recognizable to both groups. In the lines, they both see coastlines and rivers. The semiotics of the maps are shared between these two cultures, something that I think is really fascinating — that two cultures, separated by at least 20,000 years, can make a symbol on a map and recognize and share that symbol.”

How the English appropriated Algonquin maps

According to Braccio, English settlers wrote on Algonquin maps, turning them into “hybrids” from both cultures. Often, they would sign their names or even copy the Algonquin maps, claiming them as their own.

“When an English person held an Algonquin map, writing their own words on it,” Braccio explains, “they transformed the map about sovereignty and Indigenous authority into a record of private English private property and ownership. They attempted to appropriate these maps, which would go to English courts as a way of saying ‘here’s our evidence of our borders.’ ”

One example of a transformed, “hybrid” map is that of Menuncketuck, on the Connecticut coast. The map is drawn in ink by two Algonquian sachems, Shaumpishuh and her uncle Quassaquanch, for the sale of land in 1639 to the Rev. Henry Whitfield and other English colonists.

“The map was their way of defining who owned what land and which lands Shaumpishuh would retain control over after the sale,” Braccio writes in an article for Miscellany, a publication from the McNeil Center for Early American Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. “After sketching it, the sachems relayed the names of various territories that existed between the rivers and stream to Whitfield and his scribe [Jon Higgenson], who labeled the map. Whitfield then made his own document — an English-style deed — to record the transaction.”

Instead of allowing the Algonquin people to maintain the reserved land, the English claimed it. The parcel would become part of the village that Whitfield founded — Guilford, Connecticut — and eventually Braccio’s hometown. The map is included with the town’s charter from 1638, defining borders still used today.

Later, as a historian, Braccio would learn that the year before, during the Pequot War, the English and their Indigenous allies had “killed a number of people on Shaumpishuh’s land and put their heads on display in her territory,” he says. But “we have this document that we now pretend is evidence of some harmonious relationship.”

Sachem’s Head is now a spot of land where people hike in Guilford — and where “we know the records do mention at least one sachem being decapitated and their head being placed on display,” Braccio says.

Increased violence among English settlers

By the later 17th century, maps had become even more important to the English settlers. England had begun transitioning to privately held land, and the colonies soon followed. “The English felt like they had gained military control, and their numbers were growing rapidly,” Braccio says. “They begin to anglicize the landscape. They had a concentrated goal of making it feel more English and more familiar to them.”

Colonists felt pressure to find “good land,” he says, realizing, “I can be my own king in this space.” Strife and violence increased — farmers removed land markers and attacked each other with pitchforks and other tools of the trade, according to Braccio.

The Algonquin mapmakers saw an opportunity, he explains, saying, “You’re fighting amongst each other. We can provide you with the legal evidence you need in your land disputes, but we need to have a voice in these conversations.”

But by the 1680s, according to Braccio, a new wave of professional English surveyors “brought more standardized cartographic survey and land systems to the Northeast,” eliminating the colonists’ need for Algonquin mapmaking and surveying. It also ended the blend of Indigenous and English spatial cultures that were “in negotiation with each other, shifting and changing in response to the other one.”

Braccio’s next project will explore what he calls the “culture of violence” in Puritan colonial society in southeastern Connecticut and in Rhode Island — something he encountered in the historical documents he examined for his first book.

“It’s interesting to me because it presents a very different picture of these New England colonists,” he says, “not as the kind of religious people you encounter in these funny hats in Massachusetts, but as extremely violent and brutal people. Land was everything to them, and they were willing to fight over it, even kill each other over it. Land-based violence is a major part of colonial life.

“Maps may seem like these relatively stationary, archival records,” Braccio adds. “But they are part of acrimonious and sometimes lethal disputes in in the colonies over a few acres.”

“One of the things that has changed in maps is the ways that they reflect our different set of values or assumptions about the land, because that is at its heart what a map is doing.”

— nathan braccio

At top, History Professor Nathan Braccio in his office, surrounded by maps. Photo by Steven King