Above: A satellite image of an aquaculture area in Guayaquil, Ecuador. The Clark Center for Geospatial Analytics (CCGA) is working with Seafood Watch, a nonprofit based at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California, to monitor the sustainability of shrimp farming in Ecuador and other countries. (Image courtesy of CCGA)

Decade-old aquaculture project has received over $7.5 million in grants from the Moore Foundation

When you reach for that packet of imported, farmed shrimp at Costco, you might not realize that the seafood’s sustainability certification relies, in part, on a longtime research project at Clark University.

Since 2013, Clark geospatial scientists have used GIS, satellite imagery, and machine learning technology to produce landcover maps indicating where brackish pond aquaculture — human-made seafood production “farms” — may encroach on tropical mangrove habitats and coastal wetlands. The maps have been used by nonprofit organizations, including the World Wildlife Fund, the Aquaculture Stewardship Council, Seafood Watch, and Trase, to help consumers and businesses better understand which countries are abiding by sustainable seafood practices.

“When I first started, we were mapping four countries — Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Myanmar,” says Rishi Singh ’17, M.S.-GIS ’18, who joined the research team as a fifth-year graduate student. By the time he had graduated and started a full-time job as a research associate for the project, “we had expanded to 17 countries.”

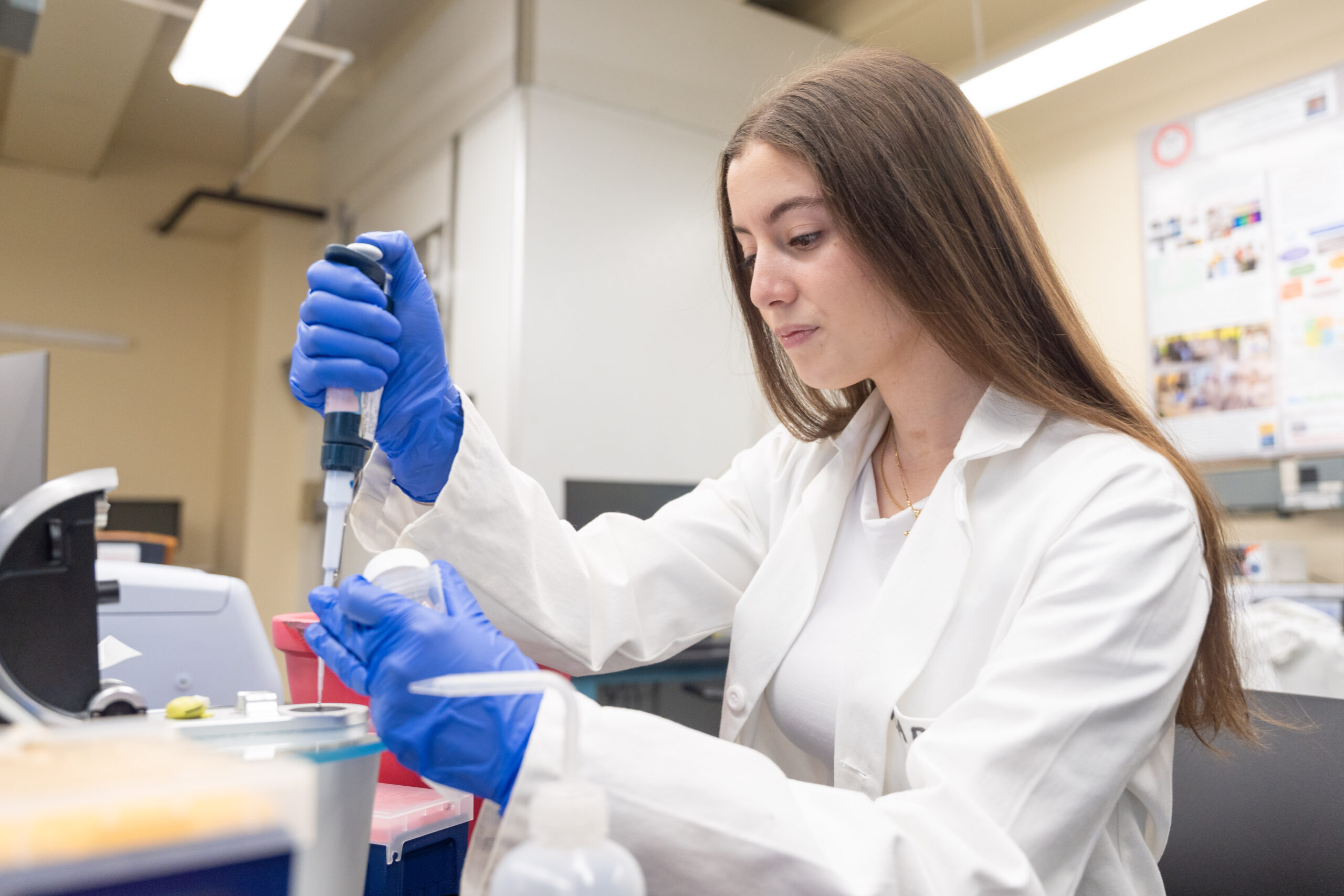

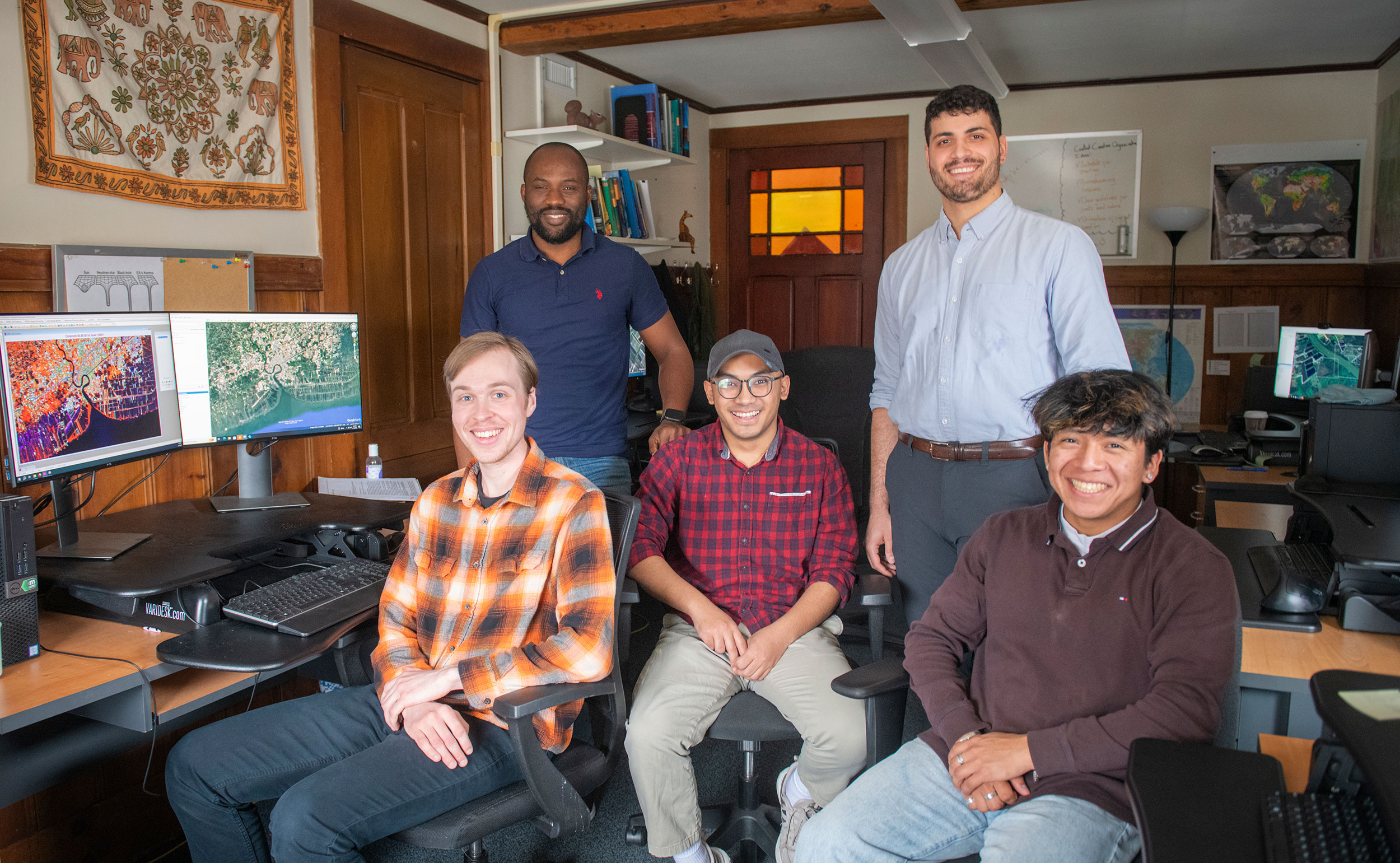

Now the project’s principal investigator and research scientist in the Clark Center for Geospatial Analytics (CCGA), Singh oversees a team of five research assistants — all graduate and undergraduate students — who are working on a new phase, “Mapping the Conversion of Coastal Habitats to Shrimp Aquaculture.” They include Adlai Nelson, M.S.-GIS ’25; Ben Gaskill, M.S.-GIS ’25; Annan Shrestha, M.S.-GIS ’26; Pacifique Madibi, M.S.-GIS ’26; Andre Bergeron’25, , M.S.-GIS ’26; as well we Clark CGA staff members Eli Simonson ’17, M.S.-GIS’18, a research associate, and Tammy Woodard, a senior software developer.

The researchers are developing maps that reflect land changes, from 1999 to 2024 due to shrimp farming in Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar, and Ecuador.

Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation: 85 percent of world’s fish stocks are fully exploited or in decline

The current project is funded by a 14-month, $717,875 grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, which, over the years, has provided over $7.5 million to Clark geospatial scientists conducting research focused on the impacts of seafood production, especially shrimp farming across the global pantropics, including Southeast Asia and Central and South America.

“Today, 85 percent of the world’s fish stocks are fully exploited or in decline,” according to the foundation. “To protect marine and coastal ecosystems,” the foundation is “encouraging leading companies to implement sustainable sourcing commitments for top-traded seafood commodities and … to eliminate overfishing and coastal habitat degradation from their supply chains, ultimately fostering responsible fishing and aquaculture as the marketplace norm.”

“The Clark Center for Geospatial Analytics’ tools have been immensely helpful for Seafood Watch to evaluate land-use change for our farmed-shrimp assessments.”

— josh graybiel of seafood watch

The Moore Foundation works closely with the World Wildlife Fund, co-founder of the Aquaculture Stewardship Council, which manages global standards and audit practices that ensure seafood farming is environmentally and socially sustainable. Scientists from the nonprofit conservation organization have relied on data from the Clark Center for Geospatial Analytics (formerly called Clark Labs) to better understand where mangrove habitats have declined — and how much.

Besides harboring a rich, diverse marine ecosystem that contributes to “blue carbon” sequestration — marine environments that capture CO2, mitigating climate change — mangroves are important to protecting coasts from erosion and storm surges, according to scientists.

“Blue carbon is a unique and extremely important part of the carbon sequestration in oceans specifically,” Singh explains. Studies have found that “a mangrove tree can sequester nearly three times the carbon of an Amazon rainforest tree.”

Over 40 years, “shrimp aquaculture has contributed significantly to the degradation of natural resources and ecosystems,” according to the World Wildlife Fund. “Global shrimp production doubled between 2003 and 2016, spurred mostly by aquaculture, which surpassed wild shrimp harvest to become the predominant source of seafood.

“Shrimp production from aquaculture increased 500% from 2000 to 2017, and today, farmed shrimp is the most valuable traded seafood commodity in the world, by volume.”

Clark geospatial data in action

The World Wildlife Fund has worked closely with global suppliers to curb the impacts of seafood production, including shrimp farming. Costco, for one, has partnered with the WWF and “has had tremendous success gearing our shrimp purchases toward ASC [Aquaculture Stewardship Council]-certified sources,” according to one of its buyers.

Data from the Clark Center for Geospatial Analytics helps companies like Costco, and their consumers, ensure that the ASC-certified shrimp they buy is truly sustainable, according to Singh. Both the World Wildlife Fund and the ASC have relied on the center’s maps indicating where shrimp farming is expanding.

For businesses, “getting that crediting is essential. Millions and millions of dollars are based on whether the shrimp is sustainably harvested or not,” Singh says. “The stakeholders use our data to back up and make decisions about whether the shrimp can be sold with the sustainability label.”

Also using the center’s data is Seafood Watch, a nonprofit organization based at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California that makes recommendations to businesses and consumers seeking to buy sustainable seafood. Seafood Watch also works with seafood producers, industry leaders, organizations, and governments around the globe to improve their fishing and aquaculture practices.

“The Clark Center for Geospatial Analytics’ tools have been immensely helpful for Seafood Watch to evaluate land-use change for our farmed-shrimp assessments,” says Josh Graybiel, senior aquaculture scientist at the organization.

“One of the most popular seafood products Americans consume is shrimp,” Graybiel says. “Much of the shrimp on the U.S. market is farm-raised and imported into the United States. Because Seafood Watch evaluates the environmental sustainability of seafood on the U.S. market, farmed-shrimp assessments are very important to our program and audiences.”

For about five years, Seafood Watch has used the center’s “Brackish Pond Aquaculture and Coastal Wetlands” interactive map to identify and define the development of shrimp farming over time.

The map allows the nonprofit to determine, for example, whether there “has been any recent conversion of mangrove to ponds and, if so, how much land area and where?” Graybiel explains.

Using Clark center’s maps to produce seafood ratings

“Using this tool, Seafood Watch is able to develop more accurate and comprehensive ratings of the environmental impact of shrimp production in key shrimp-producing countries that export to the United States,” he says.

The nonprofit has developed seafood sustainability recommendations that use colored ratings so consumers can quickly assess what to buy: Green for seafood that is “well-managed and caught or farmed in an environmentally responsible manner” and “poses a low environmental risk”; Yellow for “moderate environmental risk”; and Red, to avoid because “it’s overfished, lacks strong management, or is caught or farmed in ways that harm other marine life or the environment.”

“The development of ponds in coastal areas has been a key factor of Seafood Watch Red ratings, so the Clark CGA tool is very useful for our analyses and justification,” according to Graybiel. “Ultimately, consumers can then use Seafood Watch ratings when shopping for seafood to choose Green- or Yellow-rated seafood, a key way to make healthy choices for the ocean.”