Clark-trained teachers like the Surrette siblings bring passion, purpose, and possibility into neighborhood classrooms

Main South is to Bill Surrette as Dublin was to James Joyce.

The author had a tempestuous relationship with Ireland and left as soon as he could. But Joyce also continually invoked the Emerald Isle and its capital in his writing.

Surrette, like Joyce, couldn’t wait to leave home. At 18, the Main South kid departed Worcester for Middlebury College in Vermont, insisting he’d never look back.

And yet, here he is.

He returned to graduate in 2011 from Clark’s Master’s in Teaching (MAT) program and now spends his days at the helm of a classroom at University Park Campus School (UPCS), continuing to be inspired by Joyce as he discusses authors with the students coming of age in Main South—the same neighborhood that shaped Bill, and inside the same school he attended as a teenager.

Bill is the second of 10 Surrette siblings who grew up under challenging circumstances in Main South, their family relying on government aid to get by and crowding into small dwellings. They experienced stretches of homelessness, at one point finding shelter in a Red Roof Inn.

Through it all, they stayed close. “In a big family, you’re never alone,” says Kim Surrette ’08, MAT ’09, the oldest of the siblings. “There’s always someone to turn to.”

With little support at home, school became an escape for the Surrettes; their teachers were the stable adults in their lives. “It’s the reason a lot of us went into education,” says Danielle Surrette, M.A.T. ’21, sibling No. 7. The routine and reliability of school was a “stabilizing force,” Bill says. Kim adds, “I knew that when I went to school, I was going to laugh, and it would be a good time, no matter what was going on at home.”

The three now teach in Main South schools: Bill teaches middle school English at UPCS; Kim teaches social studies at Claremont Academy; and Danielle leads Claremont Academy’s English as a Second Language department. In total, seven of the Surrettes work in the education field.

Becoming teachers has been healing. “Some of the adults in our lives let us down,” Bill acknowledges, “and we want to help our inner child by helping kids.”

University Park Campus School is one of Clark’s six Main South partner schools.

Neighborhood Affinity

Many of Clark’s Master of Arts in Teaching graduates feel compelled to teach in Worcester. The University’s unique relationship with the Worcester Public Schools helps create a corps of teachers who are invested in the city, and in Main South especially. MAT students spend significant time in local classrooms, building bonds with students. “They develop this real affinity,” says Professor Holly Dolan, ED.D. ’17, the chair of Clark’s Education Department and director of the Adam Institute for Urban Teaching and School Practice.

A centerpiece of Clark’s collaboration with Worcester is the University Park Partnership, whose mission, in part, is to ensure Main South children can access a high-quality education. It’s through the partnership that Clark and the Worcester Public Schools created UPCS in 1997, with the University an active collaborator in developing the school’s curriculum and enrichment programs, including opportunities for high schoolers to take college-level courses at Clark.

“The partnership is collaborative and community-based, and the relationships are different because we’re intentional about building them and maintaining them,” Dolan says. “Students become immersed in the community where they’re teaching.”

In her 26 years at UPCS, Sarah Marcotte ’98, M.A.ED. ’99, has taught hundreds of neighborhood kids, including all 10 Surrette siblings. “I’ve learned more from them than they can learn from me,” she says.

“Everybody has value and talent,” Marcotte says. “Kids are all smart in their own way, trying to do the best they can, and if they aren’t doing well, something is standing in their way.”

With individual attention and hands-on learning, students in Main South are empowered to realize they have many options after graduation. For some, that means four years at Clark: The University Park Partnership includes a full tuition scholarship to students from the neighborhood who meet the University’s admissions guidelines.

Caleb Encarnacion-Rivera’17, MAT ’18, is one of those students. He grew up in Main South, attended UPCS, began taking Clark courses as a high school sophomore, and attended Clark on the neighborhood scholarship. Today, he’s the director of equity, cultivation, and recruitment for Worcester Public Schools, helping build a culture of belonging, empowerment, and agency for all students, educators, and staff.

“I knew that I wanted to eventually give back in the neighborhood where I grew up,” he says. Clark’s MAT program encourages educators to regularly reflect on their teaching practice, Encarnacion-Rivera says. As a student-teacher at South High School, he craved a better understanding of educational policy and the macro-level systems that impact classroom teaching. A master’s degree from the Harvard Graduate School of Education

put him on the path to working in school administration.

“A lot of the work that I’m doing now wasn’t in existence when I was in school,” he says. “We have grown to ensure equity work is not just something that we talk about, and that it’s sustainable for future generations.”

Teaching future teachers how to engage with students about their cultures and identities is a priority for Clark Education Professor Raphael Rogers ’94.

“They’re teaching in one of the most diverse school districts in the state,” he says. “Worcester has students from El Salvador, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Ghana, Nigeria. So, a lot of times our teachers are learning about who their students are—their backgrounds, their histories.”

Worcester Public School students speak 76 languages, and 58% speak a language other than English first, according to the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Of the city’s nearly 25,000 students, 45% are Hispanic or Latino, 24% are white, 18% are Black, and 6% are Asian. Seventy-one percent are low-income.

“I don’t think it could be ‘just a job’ for me whether I was teaching in Concord or Boston or Main South.”

Kim Surrette ’08, MAT ’09

As MAT students get hands-on experience inside Worcester classrooms and are guided by mentor teachers, they discover that teaching is not one-size-fits-all. Flexibility and compassion are part of the program’s teaching philosophy.

“We as educators need to be willing to adapt to meet the needs of the students in our classrooms, and that might mean changing how we deliver instruction—delivering the same lesson in different formats, offering students a variety of ways to show what they know, and assess their understanding of the content,” Dolan says.

The program also champions culturally responsive teaching, identifying how elements of a student’s background add value to the classroom. For Dolan and Rogers, this means encouraging their teachers-in-training to take an asset-based approach—recognizing the skills and experiences students bring to the table—rather than a deficit-based based approach that focuses on perceived weaknesses.

Rogers is working to instill in his students that it takes much more than a college degree to help children learn and succeed. Curiosity and understanding of their students are essential, he says.

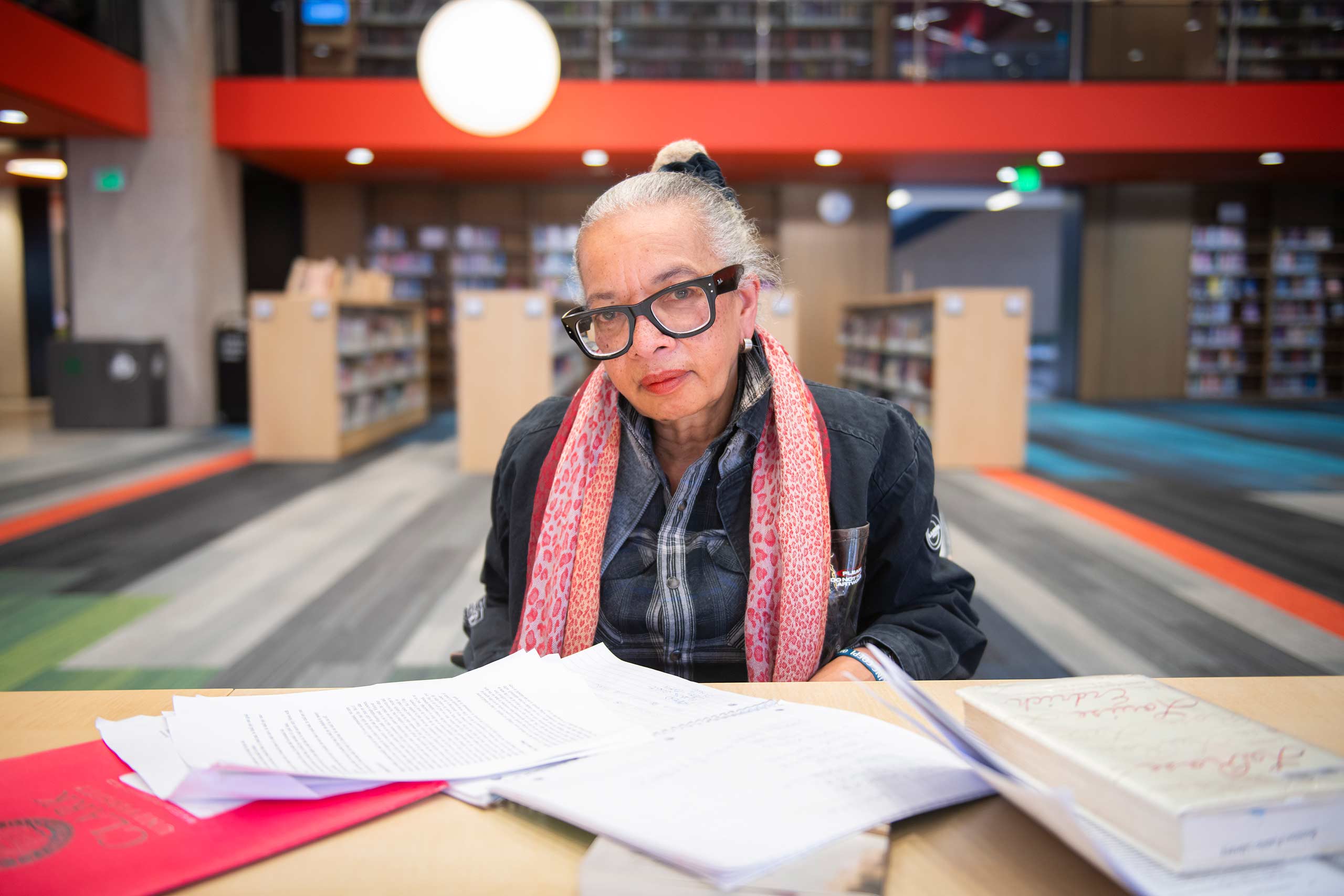

Raphael Rogers, professor of practice in the Education Department, leads a class at Clark.

Teaching the ‘Whole Child’

Before MAT students enter Worcester classrooms, Rogers presents a framework centered on holding their students to high expectations, considering the experiences of students of color in the classroom, and encouraging joy in learning.

Sammy Eagen ’22, MAT ’23, who teaches fourth grade at City View Discovery School, saw the joy in her students during a recent lesson about Madam C. J. Walker, an entrepreneur and philanthropist whose line of hair products for Black women in the early 1900s made her one of the wealthiest women of her time.

“My students were really excited to know that she paved the way,” says Eagen. “All my students who have different hair types can access hair care products that they need because of Walker. It’s something they now appreciate in real time.”

Many graduate education programs offer six to 12 weeks of student teaching, whereas Clark’s MAT program requires a full year. MAT students are paired with a cohort of learners from the first day of school to the last, and during the second half of the year they lead classroom lessons.

“I learned a lot about how to set up a classroom, how to set expectations, and how to keep those expectations high throughout the whole year,” says Eagen. “Something that Clark helped us understand is that we are doing more than just teaching content: We are teaching the whole child. My students have so many different backgrounds and needs, and it’s taken some time to figure out how to teach the same thing to all. But getting to that place has helped my students—and my teaching style.”

Feeling confident in this work deepens the affinity many Clark-educated teachers feel toward Main South and the city.

“I think many MAT students are encouraged by the impact they can have and the relationships they develop with students and their colleagues. A lot of them are interested in staying in Worcester because they want to continue to grow,” Rogers says.

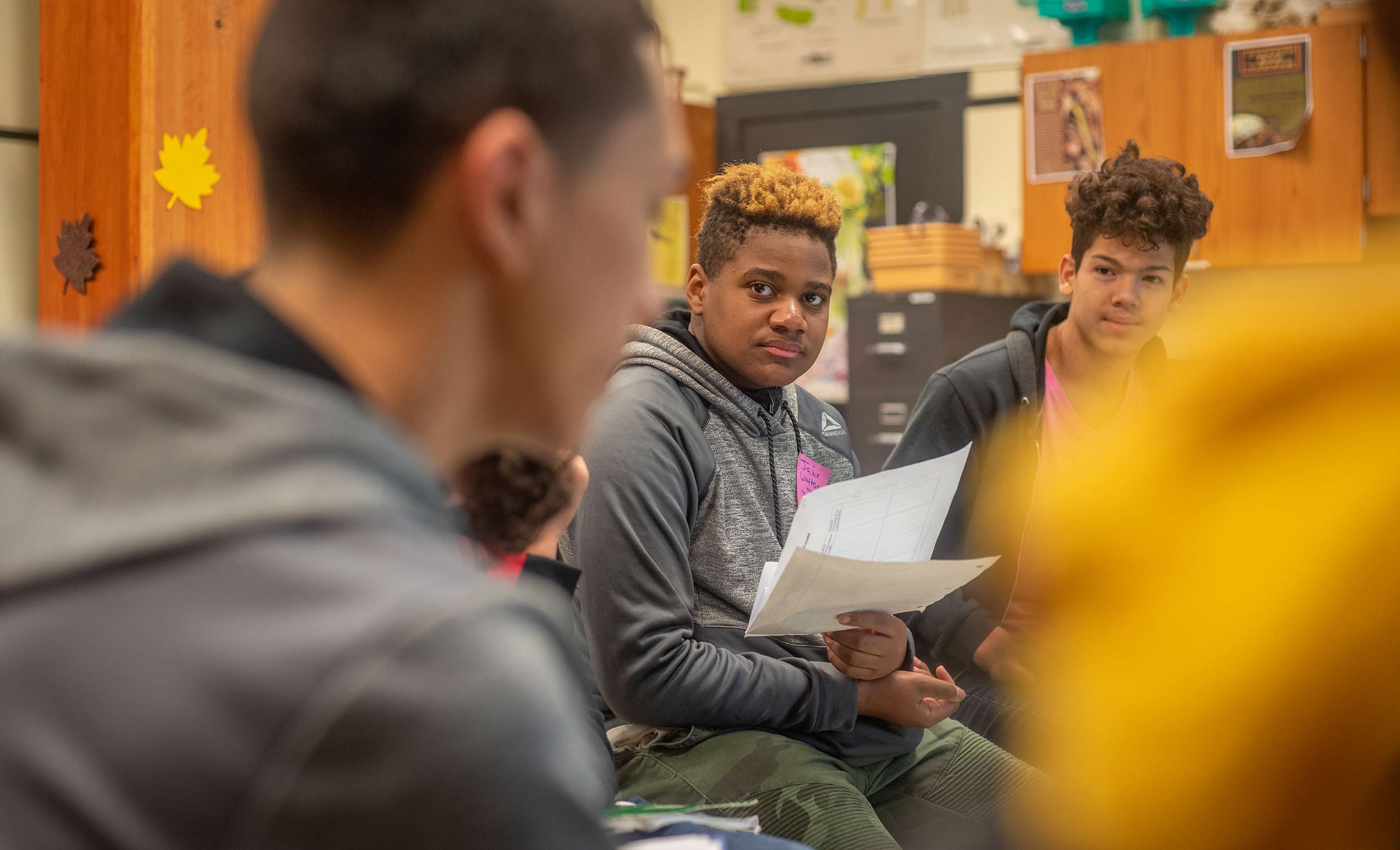

Jeremy Shulkin ’07, MAT ’08 with students in his UPCS classroom

Bringing the Content to the Students

With growth comes creative possibilities. Jeremy Shulkin ’07, MAT ’08, says UPCS gives its teachers a flexibility that some schools do not accommodate. His students finished studying The Odyssey before winter break and returned in January to start a unit on poetry including the book The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo. To help pique their interest, Shulkin had his students analyze lyrics from their favorite songs.

“Clark hammers home this idea of student-centered education,” says Shulkin, whose goal is to have his students connect to the material and be able to relate texts to the world around them. “I’m trying to make it feel like they’re the ones in control of where the class goes.”

Bill Surrette works similarly. He recently spent two months reading the unabridged version of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein with his class, who initially struggled with the dense text but got hooked by the descriptions of Victor Frankenstein’s grave-robbing practice. “This class was ready for a student-led discussion, and a bunch of eighth graders were arguing about what the nature of the soul is, what constitutes blasphemy, and whether ‘monster’ is an insult,” Bill marvels.

Kim Surrette found ways to galvanize student interest around The Federalist Papers, a series of essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison urging New Yorkers to ratify the proposed United States Constitution. Though the papers were written in the 1780s, Kimberly’s students eagerly grappled with their ideas within the context of current events.

Danielle Surrette remembers how important it was to feel safe with her teachers and looks to instill a similar measure of security and confidence in her students, even during challenging times. “I try to make sure they know that even if I’m mad or frustrated in the moment, that doesn’t mean our relationship is ruined,” she says.

It’s a meaningful lesson. The Surrettes know, far better than most, that the Worcester Public classrooms are launching pads for the future.

“It’s not just a job,” Kim says. “I don’t think it could be ‘just a job’ for me whether I was teaching in Concord or Boston or Main South.

“But here in Worcester, I can see the impact I’m making on a community that made such an impact on me, and that’s really rewarding.” □