Accession Number: 2022.02.4.24

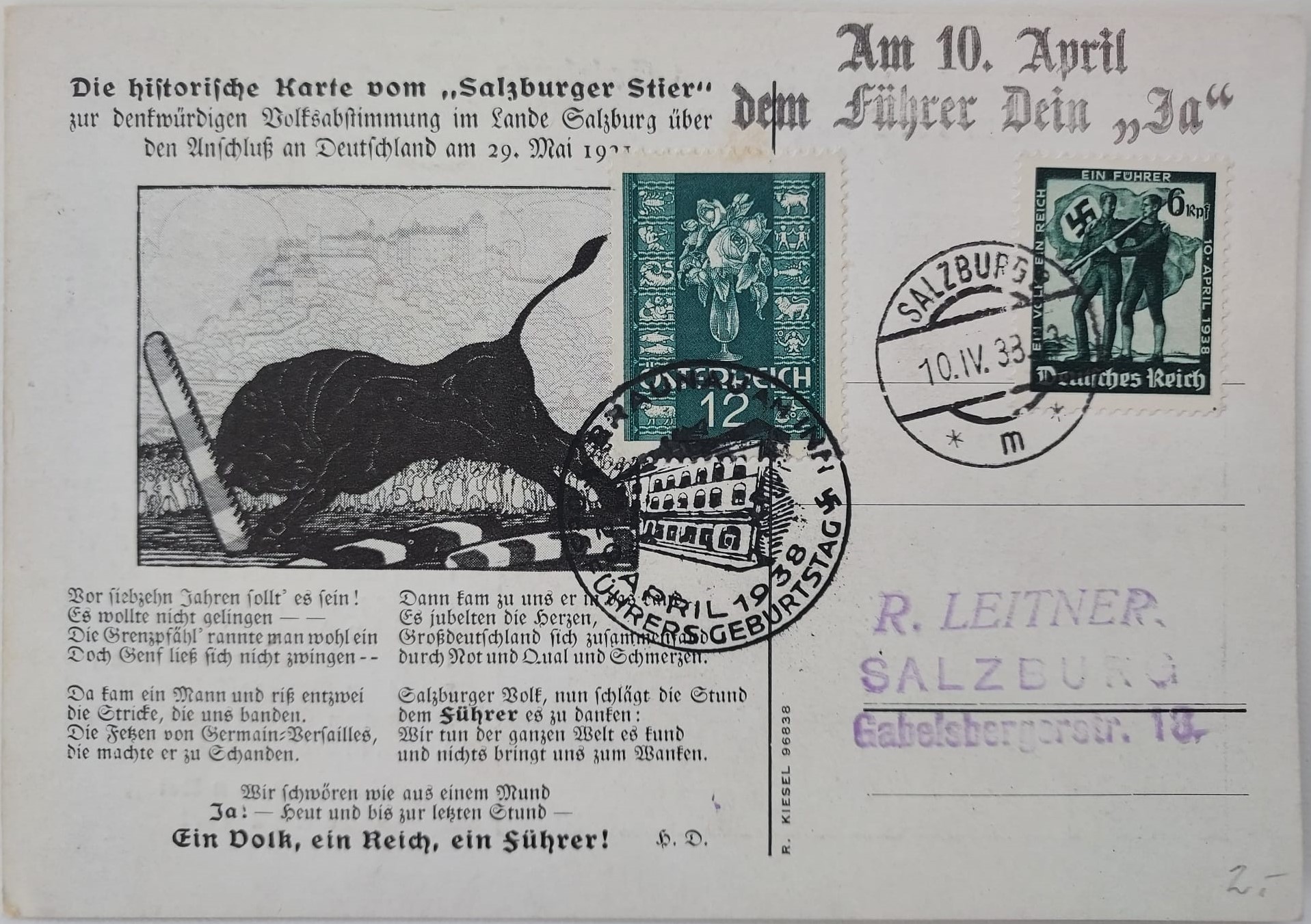

Stamp:

[right] Deutsches Reich 1938 Ein Volk ein Reich ein Führer Ersttagsbrief Ostmark b.

[left] Austria 1938 Rose and Zodiac signs

Postmark:

Am 10. April den Führer dein “Ja”

On April 10th give the Führer your “Yes”

Salzburg 10.IV.38

Salzburg 10 April 1938

Braunau am Inn

20. April 1938

Des Führers Geburtstag

Braunau an Inn (Hitler’s birthplace in Austria)

20th April 1938

The Führer’s Birthday

Historical background:

At the conclusion of World War I in 1919, the Treaty of Saint Germain officially dissolved the Austro-Hungarian Empire and forbade the creation of the Republic of German-Austria, an unrecognized ethnonationalist state claiming territory within newly-separated Austria, Germany, and Czechoslovakia. A major stipulation in the treaty was that Austria and Germany must be kept separate and not attempt to strengthen shared political power.

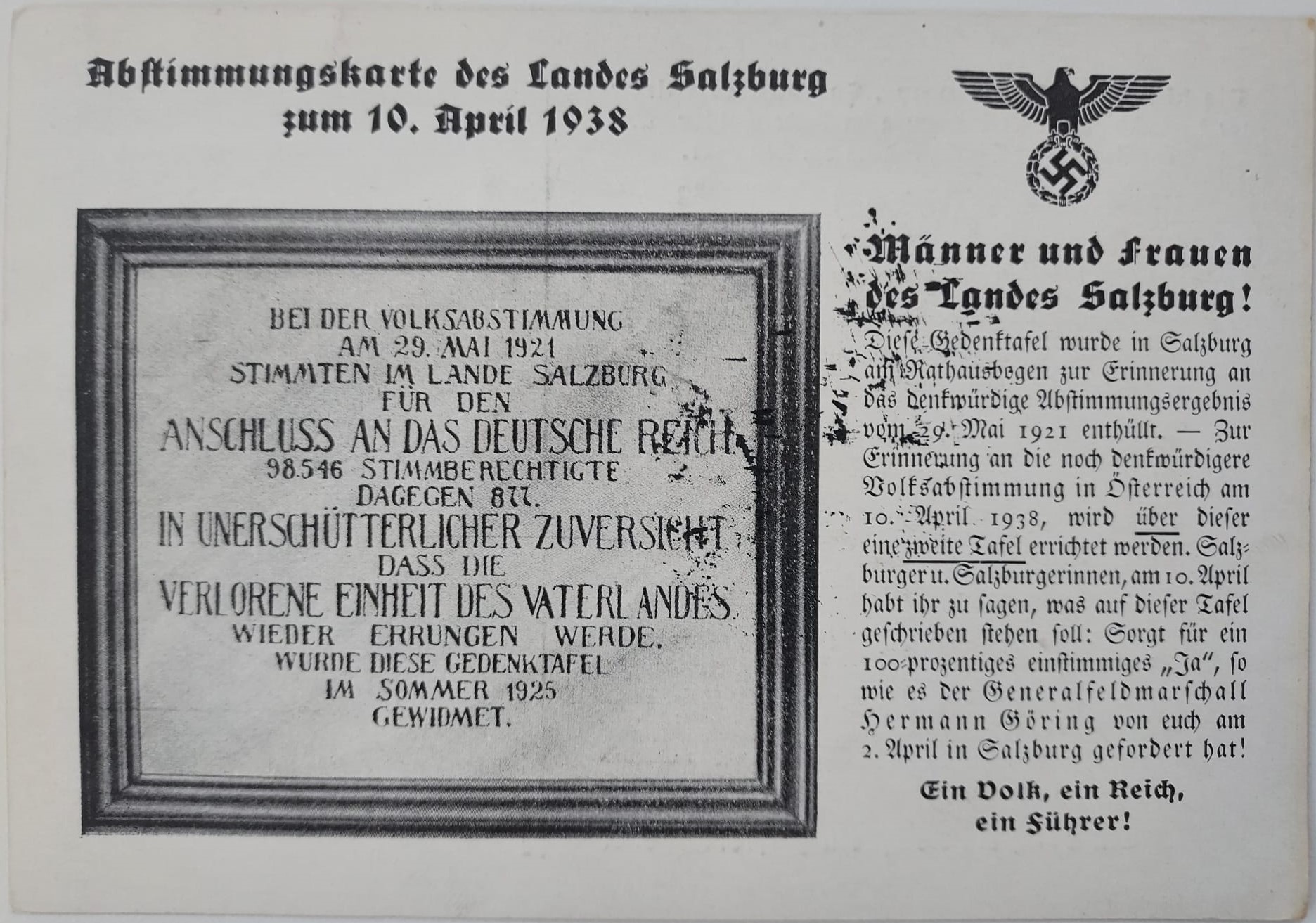

This was an unpopular change for the Austrian population (Scharf, n.d.). The idea of German Anschluss, or unification, remained widespread, spearheaded by separatist Karl Renner and his Social Democratic Workers’ Party of Austria (Gould, 1950). In May of 1921, the Constituent National Assembly (Austria’s parliament) held a plebiscite (a popular vote of national self-determination) in Tyrol and Salzburg as a symbolic motion for Austria’s desire to be united with Germany. The plebiscite asked “Wird der anschluß an der Deutsches Reich gefordert?” (Is fusion with Germany demanded?) (Salzburger Chronik, 1921). While the 1921 plebiscite did not have a tangible effect on the national status of Austria, it did generate discussion and bring awareness to the Anschluss movement. It even broke multiple New York Times headlines (NYT, 1921).

The votes were reported overwhelmingly in favor of the proposal (98.77% in Tyrol and 99.11% in Salzburg), however, these numbers are partway a reflection of the electoral fraud and voter manipulation taking place at these plebiscites (Manning, 2013). Both “yes” and “no” votes were technically permitted, but the “yes” ballots came pre-printed, and were handed to voters at the entrance. Additionally, voters had to personally hand their ballot to an election official, removing anonymity from the equation. The actual supportive population is unknown, but numbers higher than 50% defy popular estimation (Manning, 2013).

The 1921 Tyrol and Salzburg plebiscites were provincial motions unsupported by the Austrian federal government. After Salzburg’s May 29th referendum, future motions on German unification were banned. The next instance of Anschluss significance emerged in the early 1930’s. As the Nazi party gained power in Germany in the election of 1930, it sparked the attention of pro-unification Austrians who had been laying low during the 20’s. The Nazi Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer propaganda campaign worked to increase Anschluss support among both Germans and Austrians. In 1938, Hitler doubled down on his efforts to unite Austria and Germany, turning to more aggressive methods. On March 12th, 1938, Nazi troops launched a ground invasion of Austria and were greeted with an enthusiastic welcome by pro-unification Austrians (of whom there were a hearty majority after the past eight years of propaganda). Nazi troops also very effectively suppressed all voices of opposition through police force.

Two days after the invasion, the Nazis had successfully installed themselves in Austria. On April 10th, 1938, they hosted a new plebiscite. This referendum would serve to ratify their legitimacy with the popular vote. The official result was reported as 99.73% in favor. This number, of course, does not reflect the actual sentiment of the population, and is heavily influenced by violent voter manipulation campaigns.

The postcard is dated April 10th, 1938, and tells the story of the 1921 plebiscite as though it were a legitimate annexation of Austria into Germany. It is a rewrite of history for the sake of propaganda. It serves a second function as an advertisement for the 1938 plebiscite, urging voters to cast a “yes” ballot. The illustration on the card depicts the “Salzburg Bull,” the symbol of the Province of Salzburg. The poem is written in Iambic 8.7.8.7.D meter.

References:

Gould, S. W. (1950). Austrian Attitudes toward Anschluss: October 1918-September 1919. The Journal of Modern History, 22(3), 220–231.

Manning, J. A. (2013). Austria at the crossroads: The Anschluss and its opponents (Doctoral dissertation, Cardiff University).

New York Times. (1921, May 29). TO VOTE ON GERMAN UNION. The New York Times.

Salzburger Chronik für Stadt und Land. (10 April, 1921).

Scharf, M. [Accessed: 2024, September 30]. Austrian attempts to unite with Germany from the founding of the republic to the referendums in Tyrol and Salzburg in 1921.