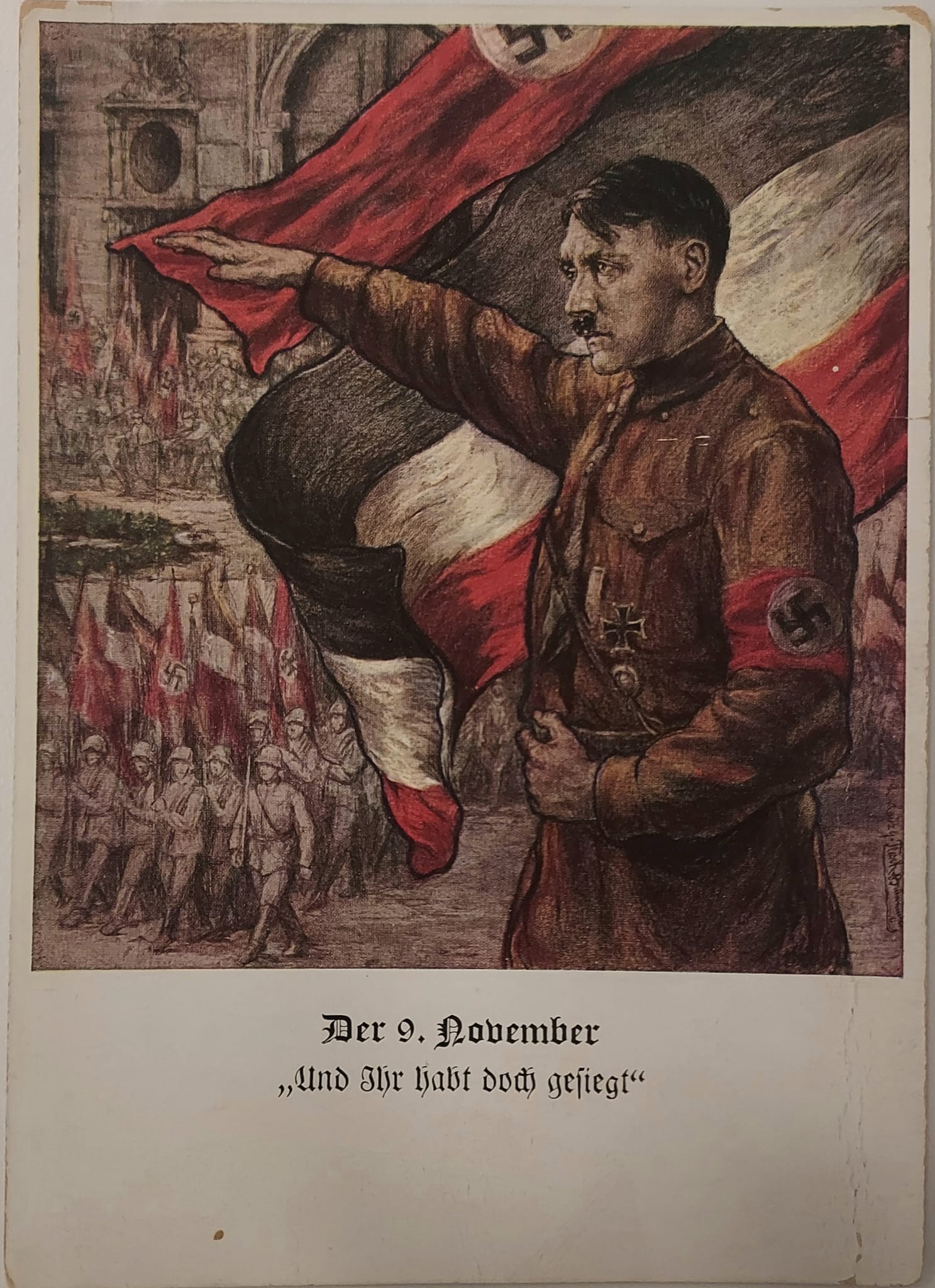

Accession Number: 2022.02.4.42

Historical background:

November 9th, 1923. Hitler assembled a ragtag militia of supporters in an attempt to overthrow the Bavarian government. They marched on the Feldherrnhalle, a stately public building in Munich and were dissolved by government forces. Sixteen Nazis died, Hitler was arrested, and the Nazi party was nationally banned (Bytwerk, 1979). In 1923, this event did not cause an enormous stir. When Hitler took power in 1933, he established November 9th as a national holiday. Each year, Hitler would host a publicized yet exclusive meeting at the Feldherrnhalle and speak before a gathering of his oldest followers. The following day, his speech would be widely published in newspapers. A dramatic reenactment of the march would be performed, embellished with grand burning pylons and blood-soaked draperies. The mood was somber: this part of the day was in remembrance of those who died in Hitler’s service. The original sixteen dead were exhumed and placed into an “Honor Temple” to keep “eternal watch” over Munich (Bytwerk, 1979). These individuals morphed into a bastion of martyrdom to be worshiped.

November 9th is an excellent example of the Nazis’ use of rhetoric to create a national myth. One rhetorical purpose for the November 9th holiday was to age Hitler’s movement. A relatively recent movement does not have a past to be revered, places and heroes to idolize. In the creation of the holiday, these themes can be crafted. They need not be supported by fact, as long as they are created and spread, they will have an impact on the people (Bytwerk, 1979). In the myth, the Feldherrnhalle becomes the setting of the ordeal in the hero’s journey (Campbell, 1949). The immortalized martyrs model what followers could one day achieve by dedicating themselves to the movement.

Bytwerk, R. L. (1979). Und Ihr habt doch gesiegt: Rhetorical functions of a Nazi Holiday. ETC: A Review of General Semantics, 134-146.

Campbell, J. (1949). The hero with a thousand faces. New World Library.